Imagine if a person with cancer could have an implant placed directly in their tumor to deliver precise doses of medicine to that specific area. Then, when the medicine is gone, the implant dissolves. Researchers from the University of Texas at San Antonio and the Southwest Research Institute are working together to make exactly that.

Mechanical engineering professor Lyle Hood, who runs UTSA's Medical Design Innovations Laboratory, said the implant — if it works the way they think it will — could change the way diseases like cancer are treated.

Personalized doses of medicine could be delivered through the implant over time as it degrades.

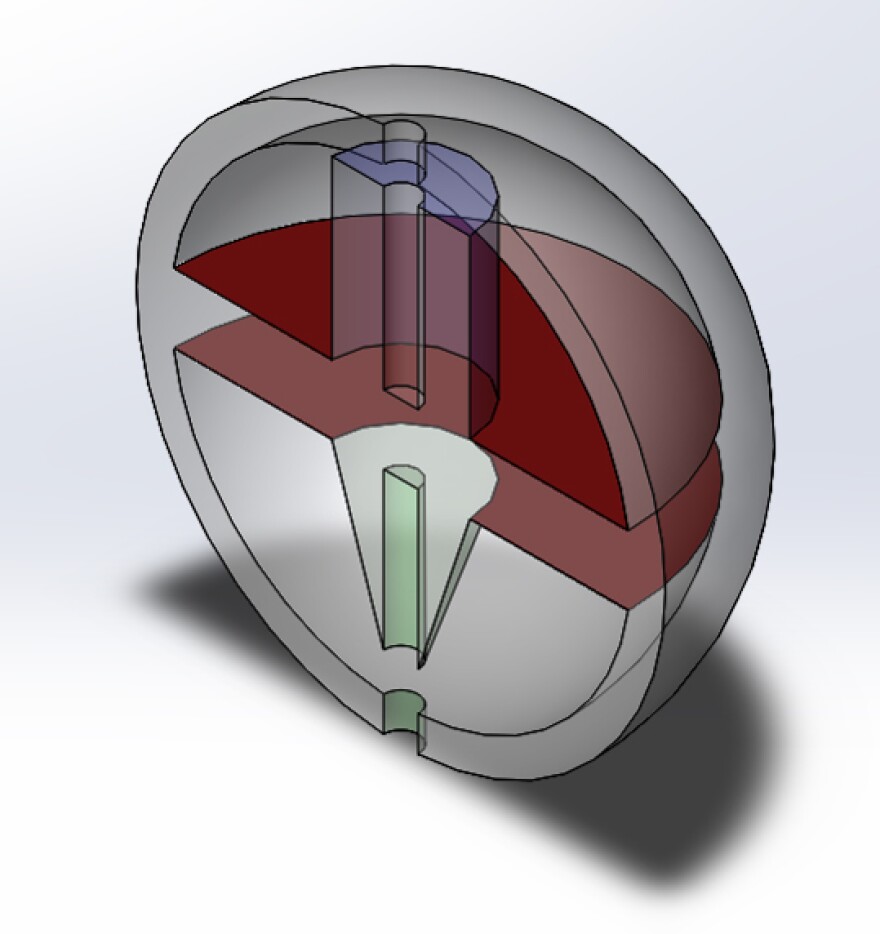

"It's a small, implantable system made of a biodegradable polymer that, as it degrades, releases a drug that has been dissolved within it," Hood said. “... Something that could be extruded from a syringe needle so it's minimally invasive and doesn't require general anesthesia and a surgery to do the placement.

“It’s small because no one wants to be implanted with a Cadillac.”

Priya Jain, a UTSA graduate student who's leading this project, said their team is responsible for designing and printing the implant, while another team at Southwest Research Institute figures out which biodegradable polymers will make the implants work the way they want them to work.

SwRI Research engineer Albert Zwiener said the implant will have a small hole in it with medication inside, as well as one of the polymers they select.

"Then the internal polymer (dissolves) away, and then that drug and your dissolved polymer are both coming out the small hole,” Zwiener said. “So that gives you some means of controlling the release rate in terms of the hole size and the polymer selection."

SwRI biomedical engineer Kreg Zimmern, who is also a part of the implant team, said if you can fine-tune how and where the medicine is delivered, treatment for cancer patients might no longer ravage the whole body.

"You give someone chemotherapy, you treat the whole system with poison to kill the one little part of it that's actually disrupting the organism,” Zimmern said. “So if we could keep that local and tunable there's the potential to have a lot less of a reaction."

While the project is focused on immunotherapy to treat cancer, Hood says if it works for cancer treatment, why not other things?

"One of the potential long-term advantages of this approach is going to be that we can print implants with predetermined drug doses specific for a patient; a larger male versus a smaller male or female is going to require different doses of the drug,” Hood said. “So if this is developed correctly we'll have 3D printers like these in the pharmacies and the pharmacist can basically do medicine a la carte."

Hood says pharmacies won't be printing out implants for the general public for 10 to 20 years. The grant for this collaboration between UTSA and SwRI on a 3D printed implant will last a year.

Bonnie Petrie can be reached at bonnie@tpr.org or on Twitter @kbonniepetrie